Ofcom publish 'Children and parents: media use and attitudes' report 2018

Ofcom have today published the 2018 version of their “Children and parents: media use and attitudes report”. The report examines children’s media literacy and provides detailed evidence on media use, attitudes and understanding among children and young people aged 5-15, as well as about the media access and use of young children aged 3-4.

The report also includes findings relating to parents’ views about their children’s media use, and the ways that parents seek – or decide not – to monitor or limit use of different types of media.

A summary can be found on the Ofcom website here.

Key findings

Media Lives by Age: A Snapshot

Devices and viewing habits

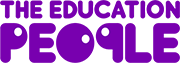

- Children in the UK (aged 5 to 15) now spend around 20 minutes more online, in a typical day, than they do in front of a TV set – just over two hours online, and a little under two hours watching TV.

- TV sets and tablets dominate device use, but time spent watching TV on a TV set (broadcast or on demand) is decreasing.

- Among 5-15s overall there has been a decrease in the use of computers, laptops, netbooks, games consoles and DVD/ Blu-ray players.

- The viewing landscape is complex, with half of 5-15s watching ‘over the top’ (OTT) television services like Netflix, Amazon Prime Video and Now TV.

- YouTube is becoming the viewing platform of choice (80% have used it) with rising popularity particularly among 8-11s;

- Vloggers are an increasingly important source of content and creativity; with the most significant rise coming from the 12-15 age group – 52% of whom now claim to watch vloggers.

- Many of the children were inspired by YouTubers and were aspiring to create content like them. Some were regularly posting their own content online; some children had a sense they might ‘get discovered’ by posting this content, and therefore often mimicked other YouTube content.

- Vloggers are an increasingly important source of content and creativity; with the most significant rise coming from the 12-15 age group – 52% of whom now claim to watch vloggers.

To help understand why children are drawn towards online content, this year Ofcom has undertaken a detailed qualitative study of children’s viewing: Life on the small screen: what children are watching and why. This finds that:

- YouTube dominates, followed by Netflix. Children in the study overwhelmingly preferred watching YouTube and Netflix, to any other platforms.

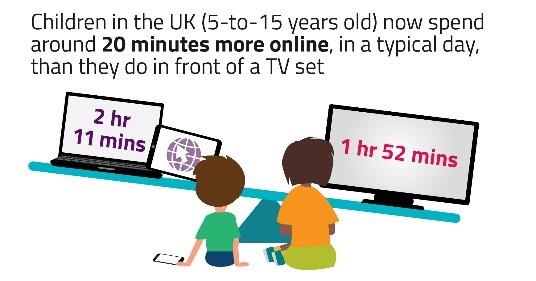

- Live TV is parent-led, and often reserved for family time. Most of the children in the study watched live, scheduled TV, though only a small number did so daily. Live TV viewing was often convened by parents, allowing the family to come together to watch soaps, quizzes or ‘appointment viewing’ such as Strictly Come Dancing or The X-Factor.

- Choice and control. Many children said they valued YouTube and Netflix for offering instant control over what they are watching, and access to seemingly endless, personalised content Children appreciated the platforms’ content recommendations and valued receiving notifications from the channels they subscribed to. Some preferred to watch content privately, whether this be on their personal devices or in their bedrooms.

- Children turn to YouTube for three things. The study found most of the children’s viewing on YouTube fell into three broad categories:

- Hobbies and passions. Lots of children watched videos related to their offline interests – such as tutorials to further their passion for music or football. Some experienced similar gratification watching others participating in hands-on activities – such as arts and craft, or playing sport – to the extent that they said they no longer took part in these activities themselves in the ‘real world’.

- Vloggers and community. Many children watched ‘vloggers’ or YouTubers, often connecting with them through a shared passion such as sports or crafts, and enjoying becoming part of their ‘follower’ community. Lots of the children said they looked up to their favourite vloggers as role models, or regarded them as a friend who could provide support or advice. This type of content also appealed to children’s natural curiosity about other people’s ‘normal’ lives; they felt the videos had an authenticity which made them easy to relate to.

- Sensory videos. Many children enjoyed videos which included ‘satisfying’ noises – such as other people making and playing with slime, or opening presents. Such videos are described as ‘Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response’ – due to their ability to generate a feeling of well-being and relaxation among some people.

Gaming and Social Media

- Online gaming is increasingly popular; three-quarters of 5-15s who play games do so online

- It was estimated that 3-4s who game do so for 6 hours 12 minutes a week and 12-15s game for 13 hours 48 minutes a week.

- Gaming has the biggest gender disparities: boys in each age group spend more hours than girls in a typical week playing games, with the difference by gender increasing with the age of the child. On average girls aged 12-15 spend around 9 hours per week gaming while boys of this age spend over 16 hours per week gaming.

- Gaming has a strong social element; close to two in five online gamers aged 8-11s (38%) and three in five aged 12-15s (58%) say they use online chat features within the game to talk to others.

- In terms of who they are talking to, they are more than twice as likely to chat through the game to people they already know outside the game (34% 8-11s, 53% 12-15s) than they are to chat to people they know only through playing the game (10% 8-11s, 25% 12-15s). Boys aged 12-15 who play online games are also twice as likely as girls to say they chat to people they only know through a game (30% vs. 16%)

- There has been an increase in the proportion of parents of 3-4s (25% vs. 10%) and 5-15s (34% vs. 29%) who play games, who say they are concerned about the content of the games their child plays.

- 70% of 12-15s and 20% of 8-11s who go online have a social media profile

- While Facebook remains the most popular social media site or messaging app, used by 72% of 12-15s with a social media profile, 12-15s are more likely than in 2017 to use Instagram (65% vs. 47%) and WhatsApp (43% vs. 32%). Fewer 12-15s nominate Facebook as their main site or app (31%). Close to a quarter (23%) nominate Instagram as their main site or app.

- Although 13 is the minimum age for most of the social media sites, 12% of nine-year-olds have a social media profile; by age 10, 21% have a profile and 34% do by age 11.

- Some children spoke with had multiple accounts on the same social media platform, which had different levels of visibility to their social groups. Children posted different content on these profiles depending on who they allowed to see each profile; more visible accounts tended to be more highly curated, showing a ‘picture-perfect’ self, while less visible accounts tended to be used to show their ‘real self’ to more carefully controlled circles of close friends.

- Social media can bring a combination of social pressures and positive influences

- 78% of 12-15s admit to feeling there is pressure to look popular and 90% said that people are mean to each other on social media, at least ‘sometimes’

- Girls aged 12-15 with a social media or messaging profile are more likely than boys to feel pressure to look popular on these sites ‘all of the time’ (20% vs. 11%) and are more likely to feel that there should be rules about what people can say online to prevent hurtful comments (77% vs. 67%).

- Nine in ten social media users aged 12-15 state that social media has made them feel happy or helped them feel closer to their friends. Two-thirds of 12-15s who use social media or messaging sites say they send support messages, comments or posts to friends if they are having a hard time, and one in eight support causes or organisations by sharing or commenting on posts.

Reliability

- TV and social media are important sources of news, but many have concerns over the accuracy and trustworthiness of news on social media

- A majority of online 12-15s think critically about websites they visit, but only a third correctly understand search engine advertising

Risk and Unwanted Content

- Children are still being exposed to unwanted experiences online, but almost all recall being taught how to use the internet safely

- One in ten 8-11s and one in five 12-15s who opted to answer the question said they had ever personally experienced some form of bullying.

- One in eight 12-15s said they had been bullied either face to face (12%), or on social media (11%). Nine per cent said they had been bullied through messaging apps or by text.

- 16% of children aged 8-11 who go online have ever seen something online that they found worrying or nasty, but at 31%, 12-15s are nearly twice as likely to have experienced this.

- Seventeen per cent of children aged 12-15 who opted to answer the question said they had accidently spent money online.

- Around one in five 12-15s (22%) who opted to answer the question said they had been contacted online by someone they didn’t know, and one in ten (9%) said they had seen something of a sexual nature that made them feel uncomfortable, either online or on their mobile phone.

- Nearly all 8-11s and nine in ten 12-15s say they would tell someone – most likely a family member– if they saw something like this online. They are also aware of, and in some cases using, other means of reporting; close to seven in ten 12-15s who go online say they are aware of online reporting functions, and 13% say they have used these to report worrying or nasty content. However, a similar proportion state that although they had seen something like this, they had not reported it (12%).

Parents

- Parental concerns about the internet are rising, although parents are, in some areas, becoming less likely to moderate their child’s activities

- Close to four in ten parents of 5-15s (38%) use such PINs on their TV service, and of those who do, more than four in five (85%) agree that they are effective

- Nearly all parents of 3-4s and 5-15s (97%) mediate their child’s use of the internet in some way, either through technical tools, supervision, rules or talking to their child about staying safe

- Among parents of 5-15s who are aware of content filters, half say they opt not to use them because they prefer to use other mediation strategies (like supervision, having rules or talking to their child) or because they trust their child to be sensible (48%).

- Eight in ten parents of online 5-15s (81%) have ever talked to their child about staying safe online

- Nearly all internet users aged 8-11 (95%) and 12-15 (96%) recall being told about how to use the internet safely, with children most likely to have received the information from a parent or teacher. However, compared to 2017, children aged 12-15 are less likely to say they have received information or advice from a parent (71% vs. 83%).

- Less than a third of parents who knew their child had a social media profile could correctly state the minimum age limit of the social networks.

- There has been an increase in parents of 12-15s and of 12-15s themselves saying that controlling screen time has become harder; however most 12-15s consider they have a struck a good balance between this and doing other things

What does this mean for education?

It's important that Early Years settings and schools consider the shifts in technology use for children; it's important that this is reflected in curriculum content, as well as staff training, to ensure that settings are able to support children online in a realistic and effective way.

The UKCIS 'Education for a Connected World' framework may help educational settings review and develop online safety education as part of a holistic and embedded approach.

Links to curriculum content and materials that educational settings can use and share with parents/carers can be found on Kelsi.